Episode 1: Fred

From a creaky door in a group home, to the flash of a gun in the dark, to a face-to-face meeting with the man who thinks you killed his brother, this is the story of Fred Clay. His episode airs on the anniversary of the day he was sentenced to life without parole — for a crime he didn't commit.

|

TRANSCRIPT

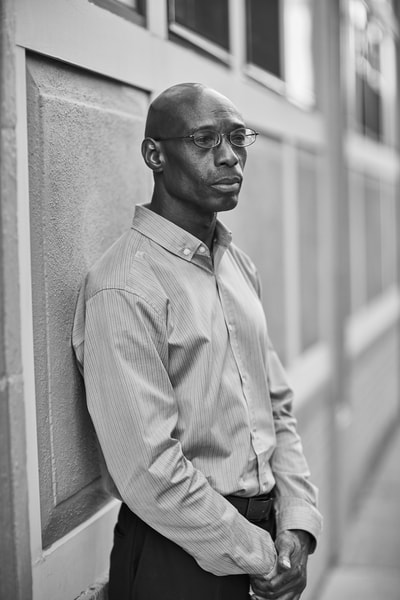

NARRATOR This podcast contains explicit language and mature content. It might not be appropriate for all listeners. F. CLAY I mean she really didn’t say she did. She never said, ‘I believe you, son. I believe you.’ She just said, ‘ok,’ ‘alright,’ ‘If you say so.’ That’s what she said, ‘if you say so.’ ‘If you say so.’ She was saying that a lot, so I thought she believed me. But I really don’t know. NARRATOR From Boston, Massachusetts, you’re listening to Mass Exoneration. These are the stories of people who were convicted of crimes – crimes they never committed – and what happened next, for them and for the people they had to leave behind. I’m Brian Pilchik. This is Episode 1: Fred. F. CLAY My name is Frederick Clay. I spent 38 years in prison for a crime I did not commit. NARRATOR When Fred was growing up, it was just him, his mom, and his siblings. F. CLAY I’m the oldest of four. I come from a single parent home. I was raised by my mother. She was an alcoholic. She obviously had some issues, I think, growing up cuz she come from Mississippi. So she experienced a lot of Ku Klux Klan events. And I think that was one of the things that sort of haunted her all of her life a little bit. Between that and the fathers of her kids not supporting her, I think that sort of drove her to drink. NARRATOR They moved. From the South, to New England. F. CLAY I think we moved to Massachusetts when I was 8 years old in 1972, and right from the start we was moving around a lot. We moved in with my great aunt at first, and after that it was like we just moved from house to house to house to house. We really didn’t have a place of our own. And every time we moved it seems like her drinking got worse for some reason. She spent a lot of time in bars. She took me to quite a few bars. And, even under the age of 10 I was like sort of grew up in bars. NARRATOR Fred struggled. At home, at school. He was the oldest. He was expected to help his mother make ends meet. So he dropped out of school, in 8th grade. He tried to pick up manual labor jobs, but wasn’t having much luck. He started shoplifting. Snatching purses. Petty crimes, to try and provide for the family. By the time he was 13, he got caught. Ended up in juvenile court, and under the supervision to the Department of Youth Services, DYS. F. CLAY In the course of me being committed to DYS, they found out that my mother was an alcoholic and so they placed me in a foster home. NARRATOR But they didn’t just take Fred. F. CLAY And my other sisters and brothers got placed in foster homes too. I thought that my situation cause them to get placed in the foster home so for quite a while I sort of blamed myself for my family being broken up. It was tough. NARRATOR It was about to get a lot worse. F. CLAY It happened shortly after I turned 16 years old. NARRATOR It was 1979. November. Fred wasn’t getting along with his foster mother. Sometimes, when he was supposed to be home, he wasn’t there. He missed curfew. She’d report that to probation, to DYS. So DYS took him out of the foster home. They put him in a DYS group home with other kids. A place where he’d be under their direct supervision. And then: F. CLAY One night, one evening, I was in the day room with everybody else. I was watching TV. The door was right there to the left. It made a creaking sound; I looked at it, and I saw two plainly clothed detectives. Didn’t pay it no mind. I went back to watching TV. Maybe 10 minutes, 15 minutes later, after they went to the main desk to talk to the counselor there, they called my name. And so I went up there. They asked if my name is Frederick Clay; I said yes. They said we need to speak with you. I said ok, and they took me to a little side room. And they informed me that I was being arrested for murder. NARRATOR A few nights earlier, a taxi driver had been killed outside of Boston. His name was Jeffrey Boyajian. Jeffrey had picked up three black men in downtown Boston. Another cab driver saw them get in and drive off. Jeffrey drove them to a dead end street in Roslindale, a neighborhood south of Boston. It was 4 AM. Pitch black. The cab stopped. The three passengers pulled Jeffrey out of the car. Rifled through his pockets. And shot him in the head. A witness told the police the shooter was left-handed. Fred was right-handed. The witness described the suspects wearing leather jackets. Fred didn’t own one of those. And the night of the shooting? Fred was four miles away, across town. Still living with his foster mother — the one he didn’t get along with; the one who complained when he missed curfew. That night, she knew he was home. She had locked him in. She reported to probation, to DYS. F. CLAY I thought there was a misunderstanding. I really didn’t know what was going on. I just knew they had the wrong person, and I was really scared. In the beginning, I thought if I continued to tell the truth that would set me free. NARRATOR It didn’t. They charged him with first degree murder. Fred was still a kid. Usually children are tried in juvenile court. They get special protections. No life sentences. Not Fred though. He was tried in adult court. In Massachusetts, when kids are accused of serious crimes, the court can treat them as adults anyway. That’s what happened to Fred. No special protections. If Fred was convicted, he’d get life in prison. JERRY My name is Jerry Boyajian & my brother Jeffrey was the murder victim back in 1979. I think of funny stories, you know, with him, and I just think of looking up to him as a big brother when I was a little kid. And so I have fond memories of him, even though we didn’t really get along, you know, on a day to day basis. And I miss him. NARRATOR Jeffrey’s family watched the whole trial. Jerry was there. He went to see what would happen to the man the police had caught; the man he thought had killed his brother. JERRY It was almost surreal cuz, you know, I was used to seeing courtroom dramas on television and so this was almost weird because I almost felt like I was on a TV show. I couldn’t quite wrap my head around the fact that they were talking about my brother. PROSECUTOR / 1981 TRIAL CLIP On November 15th, Jeffrey Boyajian, a 28-year-old male, picked up around 4 pm a cab that he rented for the evening. He was not to survive his night’s work. NARRATOR That was the prosecutor giving his opening statement to the jury. The prosecution didn’t have any physical evidence to tie Fred to the crime. No DNA, fingerprints, blood. But they had found two witnesses to testify against him. There was Richard Dwyer, the cab driver who saw three men get into Jeffrey’s cab downtown. He said that Fred was one of those three men. And there was Neil Sweatt. He was one of the witnesses who lived in Roslindale, upstairs from where Jeffrey’s taxi pulled up. He said that Fred was one of the three men who pulled Jeffrey out of his cab. And that Fred was the one with the gun. JERRY I tried following the best I could, of course a lot of the discussion was kind of like, well I’m not sure about that, I don’t know if I really understand this or that. But it was odd in things like, you know, cuz they brought in the hypnosis part. I’m always a pro-science person, so I thought ooo that’s fascinating. They’re using this interesting bit of scientific theory to help with the case. NARRATOR The hypnosis part. The police interviewed the cab driver – Dwyer. They wanted to know if he could identify the three men who got into the cab. They showed him photographs. Kids who hung around that area. Who might’ve been troublemakers. Dwyer identified one person from the photographs - and it wasn’t Fred. That’s when the police told him that they had a technique — a scientific technique — that might help identify the other two. RICHARD DWYER / 1981 TRIAL CLIP He told me about hypnosis. He told me I wouldn’t go running around the room or anything, or I wouldn’t reveal deep dark secrets, or anything like that. I wouldn’t be unconscious. And then he hypnotized me. NARRATOR This is Dwyer, testifying at Fred’s trial. RICHARD DWYER / 1981 TRIAL CLIP I pictured, in my mind’s eye I could picture the scene, that night, the scene in question. And everything sort of came into focus, you know. It was very clear to me. It was almost like a TV screen. NARRATOR He was hypnotized. Suddenly, another face from the photos looked right. Fred’s face. Now he was certain - Fred was one of the men who got into Jeffrey’s cab. It was the late 70s, early 80s. Hypnosis was all the rage. Police were using it in cases across the country. The prosecutors brought in an expert to talk about how the science was supposed to work. DR. REISER / 1981 TRIAL CLIP We can freeze the frame in some instances. We can zoom in and get a close up on objects or things in the documentary. We can turn the sound up and hear things perhaps somewhat more clearly. We can go into slow motion. We can reverse it. Typically, that’s the metaphor. NARRATOR The defense had their own expert. He argued against hypnosis. Called it a dangerous illusion. It could convince a witness that he had seen something he never saw. And then there was Neil Sweatt. The one who lived upstairs from where the shooting had happened. Sweatt had seen the shooting. From 74 feet away. At 4:15 a.m. In the dark. The whole thing had lasted only seconds. The police showed Sweatt the photographs - the same ones they had shown to Dwyer. He couldn’t identify anyone. They tried hypnosis. It didn’t work. But the police didn’t give up. They knew Dwyer had already picked out Fred from those photos. They wanted Sweatt to pick Fred, too. So they showed Sweatt the photos a second time. Told him they already knew who did it. But he still didn’t identify anyone. They tried a third time. This time they made Sweatt a deal: help us out, and we’ll make sure you and your family get moved out of the housing projects. Sweatt had been trying to leave for years. He picked Fred. The trial took ten days. Dwyer and Sweatt both testified against Fred. And then the jury heard about how Fred was right-handed, not left-handed. How he didn’t wear leather jackets. Fred’s foster mother testified. Fred testified. They explained that he was home all night on the night of the shooting. That he couldn’t have been involved. And then Fred’s fate was in the jury’s hands. F. CLAY I was waiting in the holding cell for the jury to deliberate … and I was singing a lot of songs in my mind, you know, out loud, to try to help keep myself calm and not overreact and not get upset. When they found me guilty? I was like, why is God allowing this to happen to me? The judge gave me a natural life sentence. NARRATOR Natural life. No possibility of parole. Can’t get out on good behavior. Can’t get out ever. Fred’s life was over. F. CLAY I was crying, and I was scared. 17 years old, going to a state prison with a natural life sentence for a crime I didn’t commit. Not knowing how I was gonna survive and didn’t know if I wanted to survive. And, for a brief moment, I don’t really like admitting this, but for a brief moment I thought about killing myself. JERRY At the end when the verdict was in and the sentence was made; and the judge had said, you know, ‘I hope you’re satisfied with the verdict, not from a sense of vengeance but a sense of justice.’ NARRATOR Before the trial, they kept Fred in a youth facility. But after he was convicted, they took him to Walpole, Massachusetts, to a maximum security prison. Population: 800 adult males. This is where every man in Massachusetts begins their state prison sentence. Everyone just calls it “Walpole.” F. CLAY Getting out the transportation bus and seeing the steel door electronically opening up and hearing that noise and seeing guards coming out and seeing other inmates coming in. It was very scary. I was praying to God that I can survive this and not become raped, not get raped, not get killed, not become someone’s, excuse my language, bitch, or none of that. But my first thought was, don’t say nothing to nobody, just keep to myself, just be aware of my surroundings, and just mind my business and just try to stay out of trouble. And that’s what I tried to do. NARRATOR Maximum security prison. It took Fred time to adjust — learn the ropes. F. CLAY When I first went to chow hall, I sat in someone’s seat that I didn’t know. Come to find out, people have an issue with that. These guys be sittin in the same seat for years and years and years and if someone new comes in there and they sit in they seat, sometimes they respectfully tell you, ‘that’s my seat, you need to find some other seat, so can you please move.’ Sometimes they don't tell you, they just bust you upside the head with something. So, for about 2 weeks, I stood up to eat my food with my back against the wall. I didn’t sit nowhere, until I started to feel my way around the prison. Two nights after I was there. I was on the 3rd tier and it was around 6:30 after I came back from taking a shower. These two Spanish guys was on the top tier, arguing. All of the sudden they took out some knives and started stabbing each other, both of ‘em just stabbing each other. One of them dropped, but the other one still had enough strength to pick him up and throw him off the tier. NARRATOR The guy who was thrown off the tier? He had been looking in the other’s man’s cell. Saw something he wasn’t supposed to see. F. CLAY That taught me, if I walk past anybody’s room, to keep my eyes straight. Don’t look at anybody’s cell. At all. Just keep straight. NARRATOR Prison is a lonely place. Fred’s only contact with the outside world would have to come from visits. And those were few and far between. F. CLAY The only one that came to visit me every now and then, like a couple of years, like 2 or 3 years apart, was my great aunt. NARRATOR Every two to three years. His siblings? F. CLAY I was reaching out to some of my family members, but as I said earlier, they was in foster homes themselves, so they was kind of young and they really wasn't that old enough to come to be visiting me on their own anyway. They needed their foster parent to come with them, and I don't think they was comfortable with that and I wasn't comfortable with asking. NARRATOR And his mother? F. CLAY I try to get my mother to visit me. She never did. NARRATOR Sometimes, though, he talked to his mom, on the phone. F. CLAY Even though she wasn’t really there physically for me, as far as visiting and everything, there was times I called her and talked to her on the phone. Not as often as I wanted to, but I was doing that off and on. So there was a time when I still was connecting with her through the phone. NARRATOR Fred would explain to her that he wasn’t supposed to be there. That he didn’t do it. She never said whether she believed him. F. CLAY I mean she really didn’t say she did. She never said ‘I believe you, son. I believe you.’ She just said, ‘ok,’ ‘alright,’ ‘If you say so.’ That’s what she said. ‘If you say so.’ ‘If you say so.’ She was saying that a lot, so I thought she believed me. But I really don’t know. NARRATOR With hardly any outside contact, Fred started to lose hope. F. CLAY Early on in my sentence I was young, I was scared, I was angry. I lost respect for myself, I lost respect for the system, I lost respect for my family, I lost respect for my mother, everything. And for quite a while I sort of gave up on my, my, my case and my life. NARRATOR And before it got better, it got worse. Two years after Fred entered prison, his mother was diagnosed. F. CLAY She sent me like a little card when she found out that she had breast cancer. Sent me a card, like a little poem, called, I think, Beyond the Sky that's the title of the poem. And the poem talks about passing on. She died in November 1983, and at that time I had just turned 20, and I had maybe like 2 years into the system. And even though I was 20 years old, mentally I still was a kid, and I still was a child. So I needed her at that time, and you know just to lean on and just to talk to her. So it was very painful. NARRATOR They have him a short viewing of the body. But they didn’t let him go to the funeral. Or the burial. He didn’t get to visit her grave. His mother’s grave. He hoped one day he would be able to. F. CLAY That was like one of the most important things I wanted to do, that I made a promise to myself if I, if I get out I was going to do that. NARRATOR If he ever got out. But with a life sentence, no parole? Getting out was a hard thing to believe in. F. CLAY I thought I was going to die in prison. I thought that they wasn't trying to let me out regardless of what evidence I put in their face. They wanted someone to pay for the crime. And they really didn't care who it was. To me all they was interested in was getting a conviction. They really didn't care about people being innocent. Sometimes I thought if I continued to talk to people about my case, go to a law library, talk to certain guys, get their encouragement, and talk to them about the law. And when I started doing a little bit of that, I thought maybe there was a chance of me getting out. But that frame of mind it went, it came and went. Sometimes I believed it, sometimes I didn't. Especially early on when I still had stuff in court and I was getting denied and everything, and losing hope every time I got denied. I thought that, I thought I was going to die in prison. NARRATOR Two years after his mother died, Fred reached a turning point. F. CLAY I realized that I needed to not let the time do me; I had to do the time. So once once I realized I had to do the time and not let it do me, and start focusing on myself, my life sorta started changing. NARRATOR For Fred, doing the time meant doing some work on himself. The prison offered dozens of programs. Things the inmates could do, or learn. To help them improve. Fred took a reading program, he took a program on emotional health. He took another program, and another. He finished more than thirty of them. And, overcome years of self doubt and setbacks, Fred even earned his GED. The thing about these programs? If you’re serving life without parole, like Fred? It doesn’t matter how many you complete. You’re still never getting out. So why do a program? F. CLAY Once I made a conscious decision to change, and said well, whether I stay in prison or I get out of prison, I'm determined not to be the same person I was when I came in prison. NARRATOR And while he was doing the time, he needed someone to talk to. Family wasn’t an option. So Fred looked for support somewhere else. F. SMALL My name is Fred Small. I'm a Unitarian Universalist Minister. NARRATOR A pastor. Also named Fred. F. SMALL I met Fred in the summer of 1998. Another prisoner where Fred was incarcerated was seeing a volunteer from City Mission Society, and Fred let that volunteer know that he was interested also in being visited. By that time Fred was not being visited by anybody. His family had visited him from time to time in the early years, but that had stopped. So I was eager to see Fred, and get to know him. And that's that's how I came to be his pastor. F. CLAY When I met Fred Small, a lot of things was sorta changing for the better. F. SMALL Well Fred then as now is quiet, humble, unassuming. He’s got a sly sense of humor that comes out when you get to know him a little bit. I mean we talked for hours. I would sometimes, that summer, stay for 4 hours at a time. So we talked about a lot of things. F. CLAY The war. F. SMALL We talked about prison life. F. CLAY And relationships and God. F. SMALL We talked about sports. For many years of Fred's incarceration he was in Norfolk, Massachusetts within earshot of Foxboro. He could hear the cheers from Gillette Stadium when the Patriots played. He could see the blimp in the sky. And, of course, he couldn't get anywhere close to the game. NARRATOR Close enough to hear the game. But never to go in. F. SMALL And he’s a big football fan. F. CLAY I never got to talk to people in prison about those things. So this was a welcome change for me. It was someone that I can confide in, and show my true self to. Being in prison you really not allowed to, at least for me, I wasn't really allowed to talk to people about God, talk to people about the war, talk to people about not committing certain acts. So it was a way for me to be my to be myself. So I welcomed it. I enjoyed it. F. SMALL To me as a student minister, it didn't matter whether he was guilty or not. That is, my job really as a pastor is just to offer unconditional love and acceptance, and guidance perhaps, but not depending upon whether he was guilty or not. But it was very clear to me very soon that Fred was innocent. For instance, a guilty person I think would say, “Well they didn’t have any evidence, there was no physical evidence against me.” Fred never said that. What Fred said was, “If they had had any physical evidence, I wouldn’t be here. Because I would have been exonerated by that evidence.” In other words, if they had had DNA, it wouldn’t have been his DNA. So just the way he said that, just, sounded right to me. NARRATOR Even though Reverend Small believed Fred, there was nothing he could do to get him out. That kind of help would need to come from a lawyer — or a court. And then, in 2012, the United States Supreme Court gave Fred a reason to hope. Remember, Fred had been 16 at the time of Jeffrey’s murder. A juvenile. Suddenly, the Court declared that it was unconstitutional to sentence a juvenile to mandatory life without parole. LISA It violates the Eighth Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment to sentence juveniles to life without the possibility of parole as a mandatory sentence. NARRATOR So, after 36 years, Fred was eligible. For parole. LISA Parole is a chance to get out early. Being eligible for parole just means that you have a chance to appear in front of a group of people – in Massachusetts it’s 7 - and that group of people decides whether you get a chance to be released before you’ve served your whole criminal sentence. NARRATOR This is Lisa Kavanaugh, one of Fred’s lawyers. LISA So Fred, he was sentenced to life in prison, and that meant, for him, a chance to not die in prison. NARRATOR But getting parole is hard. The Parole Board has things they want to hear. LISA A big part of it is admitting that you committed the underlying crime. So it was a huge problem for Fred to go in and say, ‘I’m innocent, I didn’t commit this crime.’ The parole board is also looking at Fred’s disciplinary record, his institutional record, what kind of programs has he completed? But the bottom line is that if you go in there and you don’t admit that you committed this crime, and you don’t say, ‘I’m sorry,’ then your chances of being released are slim to none. NARRATOR If Fred kept telling everyone he was innocent, he’s not saying he did it. He’s not saying he’s sorry. Telling the truth would not set him free. He had to make a choice. F. CLAY It was scary at the time, cuz I knew by me claiming my innocence that they could deny me on that. But at the same time it was a platform for me to tell the truth. And I wanted to do that. NARRATOR Jerry Boyajian, the brother of the victim — he went to the parole hearing. The parole board had given him and his family a heads up. JERRY It was mid-April of 2015, so it was about 5 weeks before the actual parole hearing. And they said that we had the right to come and speak for the family about how we felt about it. So over the next several weeks I sat and did various drafts of what I wanted to say. F. CLAY Most victims at the parole hearing, they make it very clear that they don't want the person getting out of prison. They want them to spend the rest of their life in prison. They make that very clear, and they make it well known that they don't want the person to get parole. NARRATOR Jerry needed to figure out what he wanted to say at the hearing. The man who he thought killed his brother might get out. So Jerry and his wife Katrina went to visit Jerry’s mother. She was Jeffrey’s mother, too. Here’s Katrina, describing what happened: KATRINA So we sat down at Jerry’s mother’s kitchen table and said ‘ok, Ma.’ Here’s what’s going on. Jerry’s gonna go and speak for the family, and what are your feelings, and kinda try and let that guide. NARRATOR What did his mom want, from this person who killed her son? Did she really want him out on the street? JERRY The first thing she said was, “it’s been long enough.” And so, and that was kinda the guiding principle. We had been told by the Victim Assistance Unit that that Fred Clay was still insisting that he did not do the crime. And I was concerned about that, you want the person to acknowledge and accept the responsibility for what they’d done. So I worried about that, and I also had just made some assumptions based on my belief that he was my brother’s killer. So I went in figuring, well he probably didn’t make any attempt to better himself ‘cause he was never gonna walk the streets again. So he was probably not gonna learn a trade or anything like that. And that maybe once he got out he would not be able to support himself and so he would slide back into a life of crime. So I was concerned about that. NARRATOR When Fred got up to talk, he did tell everyone he was innocent. F. CLAY I did not take responsibility for something I did not do. And I made that very aware of that from the start. And I let them know at the same time that I have remorse for Mr. Jeffrey Boyajian losing his life. I was very sorry that his life had to end like that, but I didn't have no part of that. I wanted them to understand that. But I was willing to take responsibility for my juvenile crimes. But I also wanted them to know that - at that time I had like 36 years in prison - so I wanted them to know that, in the course of those 36 years, I was definitely not the same person I was when I got convicted 1981. So I wanted them to see that as well, and hear the things that I changed about myself. JERRY As he spoke to the parole board and answered their questions and I learned about the fact that, yes, once he got into prison he did work on his GED, and he did learn a trade, and he did go into substance abuse counseling and so forth and so on. And I said, ok, this is not the person I thought he was. And the fact that he just seemed so mild mannered. I really started wondering at that time, you know, gee, maybe he didn’t do this. KATRINA And then to add in the folks who were there speaking in support of him. That threw us quite a bit. NARRATOR Fred had many supporters in the room: two parole lawyers - Emmanuel Howard and Jeff Harris, Fred Small, a couple from Reverend Small’s church who, by that time, had been visiting Fred for many years, and several others who’d become inspired by Fred Small to visit him. A whole team. After Fred and his supporters finished speaking, it was Jerry’s turn. By this point, Jerry was shaken. You could see it. You could hear it. JERRY / PAROLE HEARING CLIP I realize that this process is very difficult for all concerned. Not just my family, but Mr. Clay’s family and friends, and Mr. Clay himself. I find myself very moved by some of the testimony that I’ve heard today. My inclination, an inclination supported by my mother and one of my sisters, has been to trust in the judgement of the parole board. That if the board felt Mr. Clay was deserving of parole, we would not object. While we might not be at a place where we can forgive Mr. Clay for what he did, we are at a place where we can let go of our anger. NARRATOR The victim’s family wasn’t opposing parole. F. CLAY First I thought that, wow, I did not expect that. I thought they was going to oppose my parole and make it very clear that they did not want me to get out. But also thought that maybe they believe me. Maybe they look at the evidence and they see what I've been trying to tell people right from the start, that I'm innocent. Maybe they see that themselves and they believe in me. NARRATOR And the parole board? They denied it anyway. There were seven members on the parole board. Four voted to grant parole. But Fred needed five. Fred’s parole lawyers challenged that result, appealing it all the way up to the state Supreme Court. They argued that under the law in effect when he was sentenced, four votes out of seven - a majority - should be enough. While that appeal was pending, Fred’s other lawyer - Lisa Kavanaugh - tried something else. She asked the court to give Fred a new trial. She argued that the identifications by Dwyer and Sweatt were so unreliable that their testimony would never be admitted if Fred’s trial happened today. LISA Eyewitness identifications are a problem in many wrongful conviction cases, but this was extreme. They were the most troubling identifications I’d ever seen in my 20 years of practice. NARRATOR Lisa Kavanaugh again. LISA In all of the years since Fred’s trial, we’ve learned that eyewitnesses make mistakes. Sometimes mistakes happen because a witness doesn’t get a good enough chance to see the events. The social science research on eyewitness identifications has demonstrated that there are things that affect how well an eyewitness can make, can form reliable memories at the front end, when they’re watching something. So, when a witness is watching an event that goes very quickly, a mistake can happen. When they’re watching an event and it’s dark, mistakes can happen. When they’re watching an event and there’s a weapon involved, that can distract and cause a mistake to happen. And certainly, when a witness is watching from a long distance, that can cause a mistake to happen. NARRATOR There procedures that the police are supposed to follow. LISA So there’s been lot of the research on the things that police can do to minimize the chance of a witness making a mistake. Now, there are procedures that police are supposed to follow. How many pictures to include in an array, for example. It’s also the case that the police are supposed to include fillers in an array. What that means is that they’re supposed to include a number of people in the array who couldn’t possibly have committed the crime. And, there are procedures that are recommended for how the police show the array to the eyewitness. So, for example, when an officer shows someone an array or does a lineup procedure, a live lineup, the officer isn’t supposed to know who the suspect is, let alone whether the suspect is in the array or in the lineup. The officer’s definitely not supposed to keep showing the witness the same set of photographs, over and over again. And they’re definitely not supposed to tell the witness, we know who did it and he’s in this array. NARRATOR The police can’t offer to move people out of the projects. LISA That would be hugely problematic. NARRATOR And hypnosis? LISA I’m sure there are places for hypnosis to be used. But it does not belong in a police investigation, and it does not belong in a criminal trial. And I think that certainly in Massachusetts, that is accepted, that is the accepted current state of science. No one currently believes that you can actually use hypnosis to allow witnesses to do what they were told they could do in this case, which was literally to zoom in on the faces and scenes that they had witnessed, to freeze frame and look more closely, reexamine what they’d originally seen. No one believes that that’s possible. NARRATOR It turns out, our memories don’t capture the world around us like a video or photograph. LISA Human memory is fuzzy, it can be changed with suggestion. We fill in gaps with information from lots of different places. We make assumptions. And hypnosis just makes all of that worse. It makes it much more likely that we build in memories that we didn’t ever really form. And what’s worse is that hypnosis will make you believe in those memories. NARRATOR The other thing that Lisa’s team discovered? LISA There was another suspect! A kid who lived in the neighborhood, who was around the same height, same complexion, same build as Fred. And he did own a black leather jacket - several witnesses told the police that he was always wearing it, just like the shooter. And, that kid from the neighborhood? he was left-handed, just like the shooter. NARRATOR Fred’s attorneys filed their motion in court. They sent a copy to the prosecutors — the District Attorney’s office. And their office opened its own investigation into the case. Then, one day, Jerry Boyajian got a call from the DA’s office. JERRY They went on telling us about everything that they had uncovered in the previous 6 months investigating this. And we were pretty much convinced that it looked like he did not do it. KATRINA The more they told us the less doubt, because the less evidence there was. I mean it was just evaporating. NARRATOR In the summer of 2017, Fred was back in court for a hearing on his motion. Before the hearing began, the DA’s office met with Jerry and Katrina. KATRINA They walked us through in extreme detail of all of their findings and what that meant. So we knew when we went up to the courtroom that they were not going to contest the request for a new trial and also that they were going to decline to hold that trial, in a sense releasing Frederick Clay. NARRATOR The prosecutors actually agreed with the defense attorneys. Fred had not gotten a fair trial. And if they had to do it all over again, they would not have charged him. Going into court, Fred’s lawyers told him that as long as everything went as planned, the judge would release him that day. F. CLAY Being part of the system all those years, I don’t believe nothing till it happens. I’m not from Missouri, but you gotta show me. NARRATOR Fred walked into the courtroom. F. CLAY Tell you the truth, it felt good to be back inside of courtroom on that side, not being recharged with anything but just talking about me getting out. I had my supporters in the back. They saw me, they waived to me. I really didn't see the victim’s family there, but they was there. And there was some cameras there at least to the side where I think the area where the jury sit at, there was a camera crew there. NARRATOR The judge heard what everyone had to say. And then: F. SMALL She said it is my honor and privilege… F. CLAY …to say that I was free to go. NARRATOR He’d been waiting for that moment since he was 16. That day, he was 53 years old. Fred walked out of the courthouse a free man. Outside the courthouse, there were reporters and news cameras. Everyone wanted to know how he felt to finally be free. F. SMALL One of the things that Fred said the day of his exoneration when they asked him, you know, afterwards how he felt, and he quoted Sam Cooke, “it's been a long time coming.” NARRATOR Reporters asked him if he felt like celebrating. F. SMALL They wanted good TV. They wanted him to jump up and down, I mean one of them literally said, ‘well don’t you feel like jumping up and down right now?’ And Fred said, no, because I know there a lot of other guys in prison right now who are also innocent, so I'm glad for myself but I know that they're still locked up. NARRATOR Fred was also thinking about his mother. F. CLAY My mother was there in the beginning when I got arrested and all the pain and suffering that she went through as well as me in the beginning. I was kind of hoping she'll be here now to enjoy this moment. So, my whole life up until that point I brought a lot of pain and misery to our lives, so I was kind of hoping that this can make up for it, she can actually see her son being exonerated. NARRATOR And before he left, Fred sat down to talk with Jerry and Katrina. F. CLAY It was a way for me to tell them that I am sorry for what happened to their brother. He did not deserve to die like that. He was doing his job, no one should have took his life because of that. I am definitely not the person that did that, and I want them to know that. And I feel for their pain, and I’m sorry. So, for me it was sort of like therapy, it was like taking some of the weight off my back, some of the anger off my back. Just telling them about that, letting it go. And I think it was a way for them to heal also. NARRATOR Since his release in 2017, Fred has been busy. F. CLAY With the help of Fred Small here, climbing Mountain Monadnock. Never did that before. Which was very exciting, very dangerous, but very exciting. Going to the beach. Speaking to some of these colleges: Boston College, Lesley College, Harvard, Harvard Medical School, Harvard Law School, doing those things. Going to the movies; I haven't been to the movies since 1978. Going apple picking and stuff like that. NARRATOR And remember those cheers he heard from the football stadium, when he was in prison? Now, he got to be a part of them. F. CLAY Going to the Patriots game, the second game of the last season, when they played Buffalo. NARRATOR When they heard Fred’s story, the Patriots invited him to a game. F. SMALL They invited the two of us to the game, and gave Fred sideline privileges during the warm-ups beforehand. And we went to the Patriots Hall of Fame and the Patriots won. It was a good day. NARRATOR Fred got a job working with machinery in Lowell, Massachusetts. F. CLAY I'm slowly grinding excess material off of parts to make it fit a jet or plane, which in my case I have been doing a lot of parts to planes and jets. So stuff like that, just grinding excess material off certain machinery parts so it can fit. I like working with machines. I really don’t like particularly getting dirty, but that’s part of the job anyway. But I always liked working with my hands. I like machinery work. So it's a trade and also it’s a good trade. NARRATOR But readjusting to life outside of prison isn’t easy. From his teens to his 50s, Fred had been conditioned to follow prison rules and schedules. F. CLAY I knew that there was going to be some type of institutionalized behaviors that I have when I came out of prison. Something that you do consistent every day, it's becoming a habit. It's going to be a part of your life. NARRATOR He remembers waking up in freedom: F. CLAY Waking up, thinking it's count time. Standing up at 7:00 with my light on in the middle of the room. I did that like 5 times. NARRATOR Count time. When the prison guards come by to count everyone inside. Or shower time: F. CLAY They give you certain time to take showers, so if you caught in the shower a minute before the shower time, you can get in trouble. So I found myself waiting until 7:00 sometimes, waiting til 8:00, even waiting until 9:00 to take a shower, when I was supposed to. NARRATOR He would keep checking for his ID. F. CLAY Everywhere you go, you have an ID clipped to you. And if you leave your cell without your ID the officers definitely let you know. They will write you up. So I found myself searching for my ID every time I left my room, even though I’m not in prison. So there’s things I did all these years every day. It’s a habit. NARRATOR On the outside, everything is a little daunting. Fred has more options to choose from than he’s ever been used to. F. CLAY There’s a whole range of toothpaste that people use. You go in the store, they got all kind of different – all I want is toothpaste that will keep my teeth white and the tartar down. I don’t care what brand it is. As long as it does what it’s supposed to do. But there’s all kinds of brands of toothpaste. With the food too, it was just figuring out the choices. Whole variety of foods and everything else that I have to choose from. In prison you didn’t have that. You stick to one particular brand you know you like. I buy the same stuff every week, every week. Out here, there’s so much variety. Everything look good. You wanna buy everything, but you can’t. So it’s just figuring out what you want, what you like. NARRATOR Crowded spaces can be tricky to navigate. F. CLAY The crowd itself, it doesn’t bother me. But when people bump into me. I saw a lot of people get bumped into in prison, especially in chow hall, when a commotion breaks out, a fight breaks out, people bump into each other and they stabbing each other, or punch you or whatever. So, when people bump into me, I get all those flashbacks. NARRATOR Fred was 16 when he was taken away. Now, he has to learn how to be an adult on the outside. F. CLAY I still get depressed nowadays, and I think about not only the time I lost out of my life for something I didn’t do, but I get angry because I’m trying to learn survival skills. How to simply fill out a withdrawal slip for the bank, or a deposit slip for the bank. Things I should have learned many, many years ago. I find myself doing that at the age of 54 now, and it’s like, this is depressing for me. Things are not the way I want to be, but, as I said earlier, I’m definitely not where I used to be. I’ve grown a lot, and my life has changed a lot. And so I want people to understand that me going to prison for something I didn't do was obviously a injustice for me. But I want people to understand too that if I got caught up in the anger, I would have been dead a long time ago, ‘ cause I would have gave up. NARRATOR And Jeffrey’s family — they’re happy Fred was exonerated. JERRY I want him to know how sorry I am he had to go through all of this. I feel, representing my family, I feel like I have a responsibility to see that he does well from here on out. I guess I want him to know that we’re thinking of him -- KATRINA All the time -- JERRY All the time. I hope that he’s having a good time and we’re glad that he has a second chance at life. NARRATOR After 38 years, Fred made it. But there was someone who was missing. Fred went to fulfill the promise he made when his mother died, more than 30 years earlier. He finally went to see her. F. CLAY My mother don’t have a tombstone on her grave, so we had some difficulty locating it. But once I called the cemetery and talked to one of the people in the office, they told me they gonna mark her grave, they gonna put a flag on her grave, a small flag with her name on it. It was very emotional. It was, for me, just to apologize to her for all the hurt and pain I caused her in her life. To a let her know I loved her, to let her know that even though she was a single parent and she had an addiction to alcohol, she tried her best, you know. She tried to give me some values, she tried to give me some guidance and some structure in life. It wasn't always the way she wanted it, and always the way I wanted it. But you know, she she tried. And it took me a long time to see that and to recognize that. So it was a way for me to let her know that I understood. F. CLAY I'm trying to build a future based on what happened to me in the past, and it's not easy. NARRATOR You can learn more about Fred — and see videos from his trial and photographs of him now — at massexoneration.com. We’ve got more episodes for you. Subscribe; follow us on social media. Mass Exoneration is produced in collaboration with the New England Innocence Project, fighting to free people in Massachusetts, Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, and Rhode Island. To help them provide lawyers to people like Fred, visit newenglandinnocence.org. Mass Exoneration is recorded at the PRX Podcast Garage in Allston, Massachusetts. Their community recording studio provides equipment and training to storytellers, producers, and editors. Thanks to Alex and Ian for all of their support. You can learn more about what they do at podcastgarage.org. Lisa Kavanaugh is our Executive Director. Jeff Harris composed our theme. Ken Richardson takes our photographs. Betsy DelCiampo created our logo. Special thanks to Andrea Peterson, Jeff Harris, Meaghan Sheridan and Tim Clarke for their help with this episode. Our podcast is edited and produced by Nicole Baker and me, Brian Pilchik. F. CLAY I’m Fred Clay, and this is Mass Exoneration. |

Resources

CASE SUMMARY |

|

Frederick Clay, National Registry of Exonerations

NEWS COVERAGE |

|

Roslindale Man Convicted Of Murder Is Freed After 38 Years In Prison, WBUR (2017)

Frederick Clay wins freedom, innocence back after nearly four decades in prison, Boston Herald (2017)

Murder Conviction Vacated, Man Now Free After 36 Years In Prison, CBS Boston (2017)

'I Lost 38 Years of My Life': Man Wrongly Convicted of Cab Driver's Killing Released, NECN (2017)

Frederick Clay wins freedom, innocence back after nearly four decades in prison, Boston Herald (2017)

Murder Conviction Vacated, Man Now Free After 36 Years In Prison, CBS Boston (2017)

'I Lost 38 Years of My Life': Man Wrongly Convicted of Cab Driver's Killing Released, NECN (2017)

CONTACT US |

|

If you have questions or words of encouragement for Fred, we can pass them along.